We can’t see or feel atmospheric pressure but rely on barometers to tell us how the pressure is changing.

Pressure changes with altitude. Changing weather patterns can also lead to changing atmospheric pressure.

For these exercises, you will need to download the phyphox app onto your phone or, if you are working in small groups, onto one person’s phone.

You will also need a tape measure (5m) and access to an open stairwell – the higher, the better!

Using the following information, calculate the theoretical atmospheric pressure at the surface of the Earth:

Total mass of the atmosphere: 5 x 1018kg

Radius of the Earth: 6370km (OR surface area of Earth = 5.1 x 10 14 m2)

Gravitational field strength, g = 10 ms-2

Pressure = force/ area

Pressure = mass x g/ (4 pi r2)

Pressure = (5 x 1018 x 10)/ (5.1 x 10 14)

Pressure = 98057 Pa

Alternative units: 1hPa = 100 Pa

1 millibar (mbar) = 1 hPa

Now open the app and select pressure:

Now use the forward arrow to start measuring the pressure:

Record the current air pressure in your classroom in Pa __________________________________

What proportion of the theoretical atmospheric pressure you calculated above it this (express your answer as a percentage)?___________________________

Move to an open stairwell and complete the following table, using a tape measure to record the vertical distance you have ascended between each measurement you make. Make sure that you make your first measurement at floor level.

Now draw a graph of change in atmospheric pressure (dependent variable) against height (independent variable).

Complete the following sentence “A pressure change of 1hPa indicates an altitude change of ____m”.

Extension Questions

Many smart phones, watches etc. are equipped with pressure sensors so that they can be used to calculate altitude.

1) If you used a phone (in flight safe mode) to measure the pressure inside an aeroplane in flight, why won’t it give you an accurate indication of the height you are flying at?

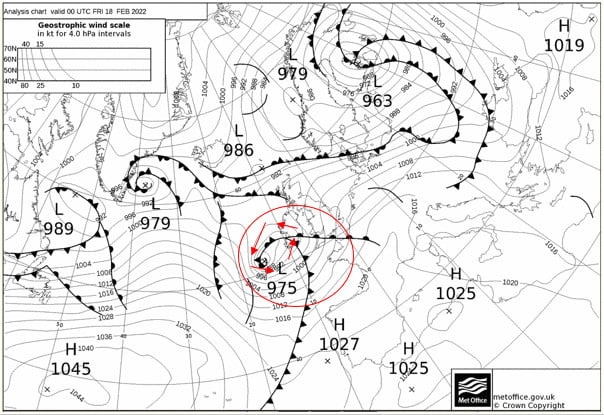

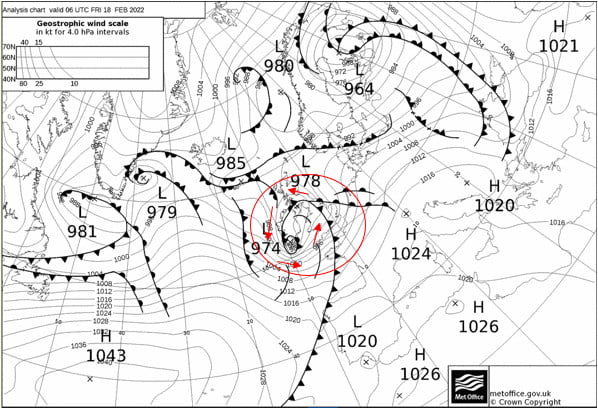

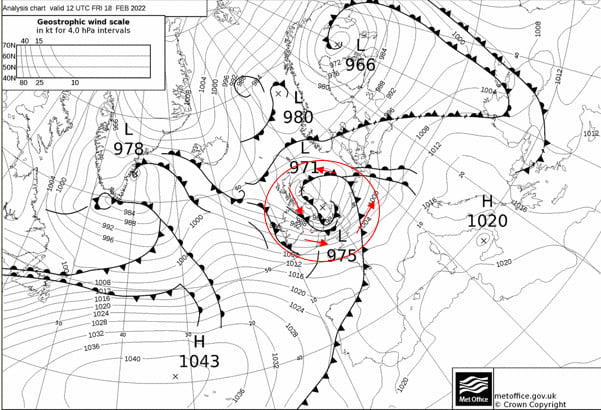

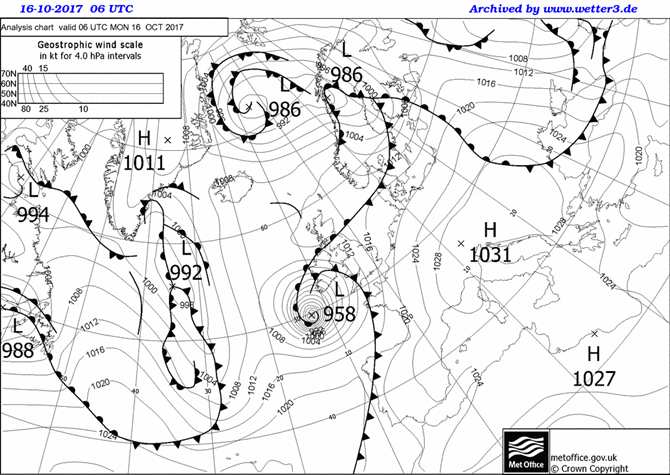

2) You are on a many-day expedition to the Himalayan mountains and you are using the pressure sensor in your watch to tell you how high you are. Why would it not be safe to rely on this information?

(resources created from ideas on https://phyphox.org/)