What are the requirements for snow?

There are three main requirements for snow, these are:

- Moisture

There must be water vapour in the air for clouds to form. In the UK, surrounded as we are by sea, this is rarely a problem. As water warms up and cools down more slowly than land, the sea around us stays at a pretty constant temperature all year round and is a constant source of water vapour into the air above, through evaporation.

It can be ‘too cold for snow’ in the centre of large land masses, such as Eurasia, Antarctica or N. America, where the wind has not encountered liquid water from which water can easily evaporate. It’s really ‘too dry for snow’ – but it’s too dry because it is so cold that the rate of evaporation from the lakes and rivers, which may be frozen, is very, very slow.

- Cloud

For clouds to form, the rate of evaporation must be lower than the rate of condensation. Evaporation and condensation are going on all the time, but the rate of evaporation falls as it gets colder. So, clouds can form when the air cools – there are several possible mechanisms for this

- Where warmer air meets colder air at a front, causing it to rise. As the air rises, the air pressure falls and so the air cools (this is known as adiabatic cooling).

- When air from somewhere colder than us (i.e. Arctic maritime of Polar Continental air masses) approaches the UK, is warmed from below as it travels over relatively warm land or sea which causes it to rise and cool. This is the most common source of snow in the UK.

- When air is forced to rise over the coast, hills or mountains and, as it rises, cools. This mechanism can add to, or enhance, the formation of cloud by either of the other mechanisms above.

- If the ground cools overnight, the air in contact with the ground can cool to the temperature at which cloud forms. This is fog and is not likely to produce rain or snow.

- Temperature

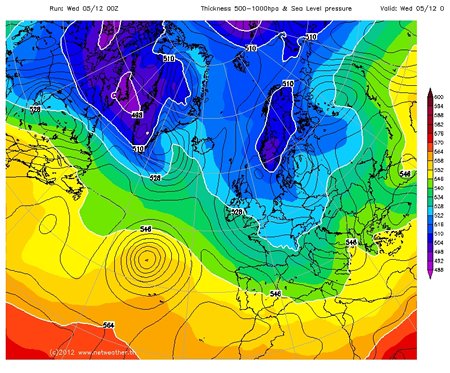

It has to be cold enough for the cloud droplets to grow as snowflakes and to not melt as they fall through the atmosphere and down to the ground. To see whether this is the case, forecasters look at the 528dam (=5280m) line. This line shows where the vertical thickness of the bottom half of the atmosphere (by mass) is 5280m i.e. the vertical distance between the 1000mb height (somewhere near the ground) and the 500mb height (somewhere in the middle of the troposphere). As warm air is less dense than cold air, the smaller this distance, the colder the air is.

If we are north of the line (i.e. the thickness is less than 528dam) then any precipitation can fall as snow, and if we are south of the line (i.e. the thickness is greater than 528dam) then we get rain.

If you look at the surface pressure forecast charts on the Met Office website, then if you go more than 24 hours into the future the thickness lines are shown. The 528dam line is shown as a blue dashed line, and the thicker/ warmer 546dam line as a green dashed line.

Another way to find out is to look at the weather forecast charts (in the charts and data menu) at http://www.netweather.tv/index.cgi?action=nwdc;sess= and select ‘HGT 500-1000’ from the ‘select chart type’ menu If the 528dam line is South of where you are, and there is a forecast of precipitation, then that precipitation is likely to be snow.

It is also worth having a look at a cross section through the atmosphere for example at http://www.wetter3.de/ – select ‘Vertikalschnitte’ which gives a longtitude/ height cross section for 50N (move the pointer on the right side of the left hand map to change the latitude of the cross section). The air between the clouds and the ground has to be cold for snow to reach the ground.

Lesson Idea

Using the information above, can your students identify which countries/ regions should have a forecast of snow? At the basic level, they can just look and see where is inside the 528 line. More advanced students should try to predict where there will be precipitation.

Nullschool is a great resource for visualising air flow and air masses.

When do we get snow in the UK?

More information from the Met Office about Snow in the UK and forecasting snow.

A nice explanation of why we had such a different November in 2011 to the weather in November 2010 from the Met Office and a report on the 2010 snow and its impacts on the UK.

And an article from the BBC about what constitutes a white Christmas.

Snow inspired science teaching ideas from Science in School.

Dreaming of a white Christmas – an article from MetMatters

Snow inspired geography teaching ideas from the GA.

How to make a snowflake, from the Institute of Physics

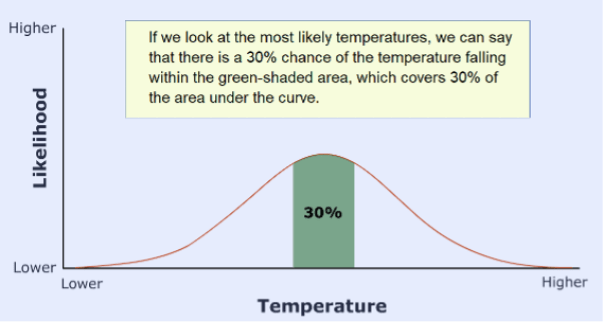

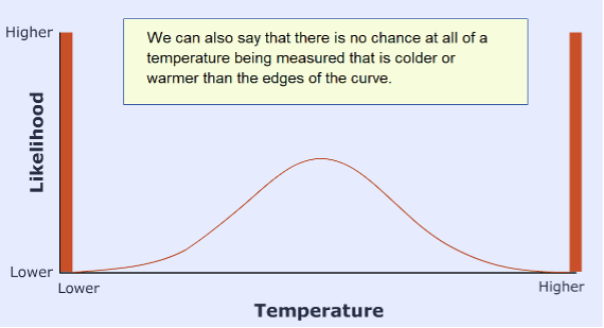

From Brilliant Maps; the probability of a white Christmas across Europe