In this teachers’ guide and the accompanying online teaching resources, we aim to give UK geography teachers all that they need to deliver relevant, engaging and thorough weather and climate lessons to 11–14+ year old students. They are not linked to any specific curriculum but should be easily adaptable to all.

In this teachers’ guide and the accompanying online teaching resources, we aim to give UK geography teachers all that they need to deliver relevant, engaging and thorough weather and climate lessons to 11–14+ year old students. They are not linked to any specific curriculum but should be easily adaptable to all.

The book is accompanied by high quality online background information/professional development resources for teachers.

The Royal Meteorological Society believes that:

- all students should leave school with basic weather literacy that allows them to understand the weather that affects them, their leisure activities and the careers they choose to follow

- every student should leave school with basic climate literacy that would enable them to engage with the messages put forward by the media or politicians and to make informed decisions about their own opportunities and responsibilities.

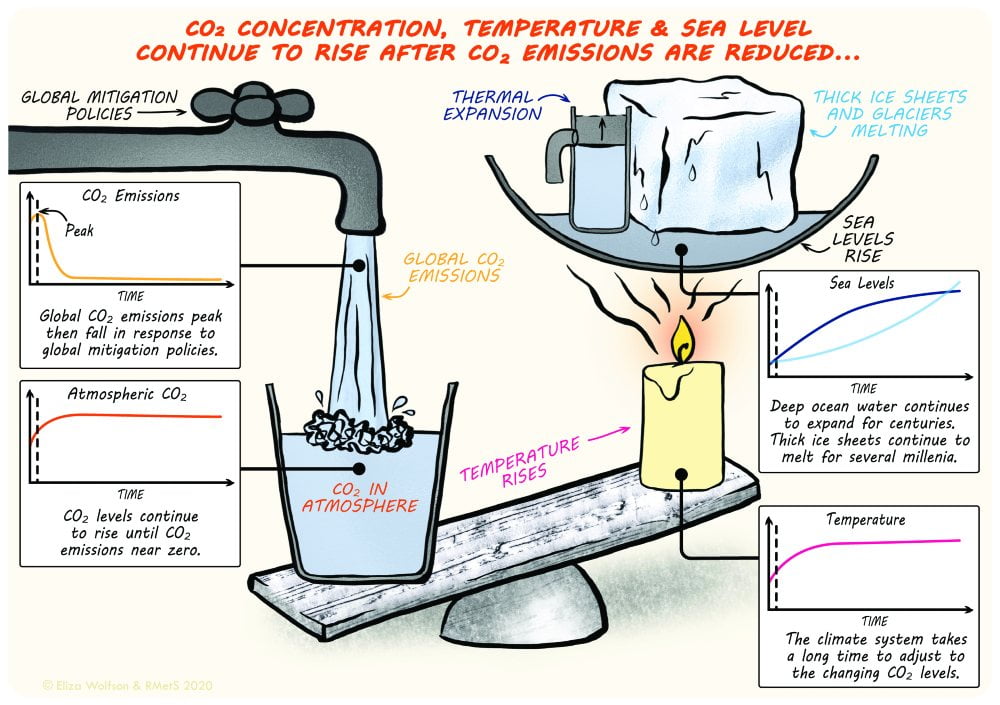

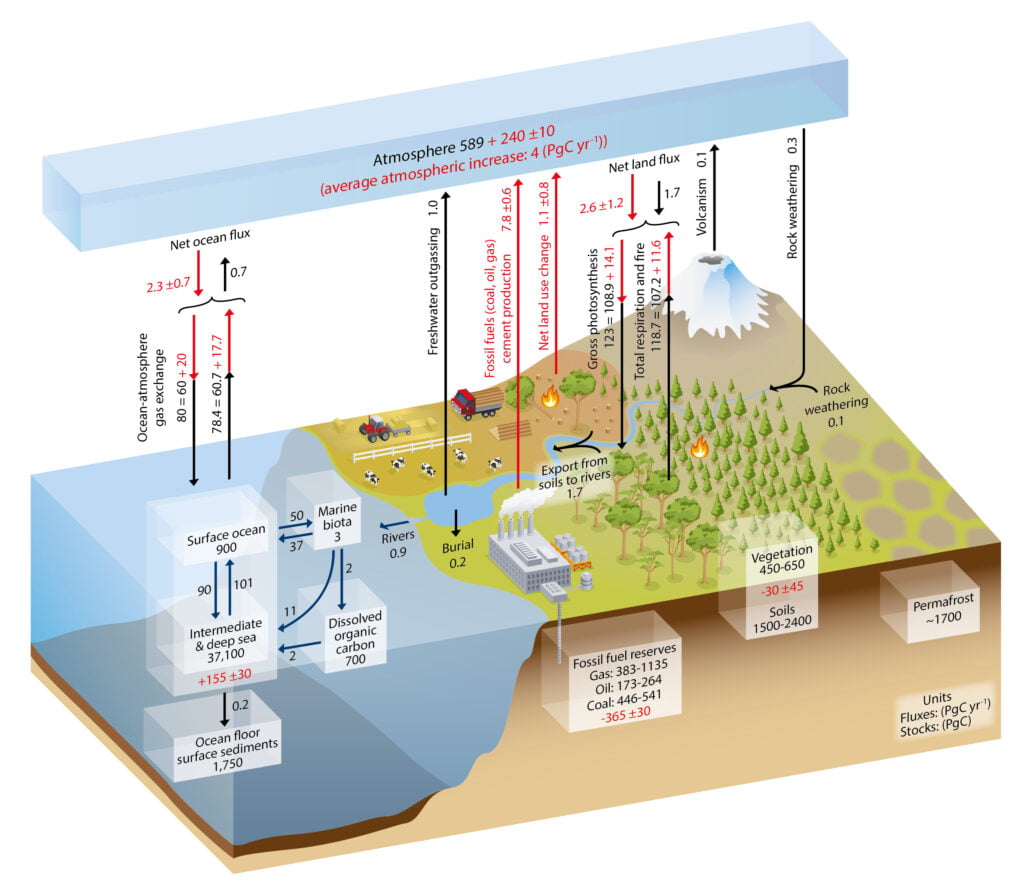

To this end, we have embedded a climate change thread throughout the online resources, showing its relevance to both weather and climate. An understanding of weather and climate is fundamental to an understanding of climate change.

There is a progression of knowledge through the topics, supported by review and assessment activities. The resources also progressively develop key geographical skills such as data, mapwork, GIS, fieldwork and critical thinking.

In this guide, we include common misconceptions which should be challenged in the classroom.

There are 20 topics or chapters. Across these, there are three threads or paths which can be taken through the online resources, depending on the teaching time available:

Basic weather: Weather in our lives, weather measurements, weather and climate, global atmospheric circulation, global climate zones, air masses, pressure and wind and water in the atmosphere

Climate: Weather and climate, global atmospheric circulation, global climate zones, past climate change, polar climate, hot deserts, changing global climate, UK climate, changing UK climate, the climate crisis

Extending weather: Anticyclones, depressions, microclimates, urban weather, tropical cyclones.

Many of the online teaching resources are available with standard or easier versions, as well as extension or alternative activities.

Find the scheme of work, teaching resources, background information for teachers, as well as the Teachers’ Guide (copies of which may be printed on request), here.

All the online resources will be updated and revised regularly.