Weather around the world

Key Stage 2 Geography

What will the weather be like on holiday and how will it affect us?

Overview

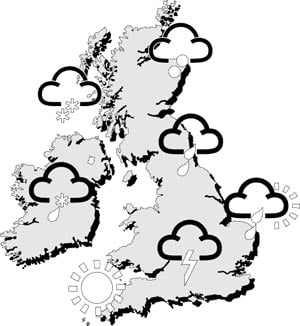

In this activity the children use a range of activity cards to learn about five holiday destinations with different types of climate, and to link tourism and human activity to the weather in each locality.

The activity can be differentiated through a choice of activity cards describing climate through a simple statement, a more detailed explanation, and graphs of average weather conditions.

Objectives

Children should learn:

- to ask and respond to geographical questions

- to use geographical vocabulary

- about weather conditions around the world.

- Lesson plans

Introduction

Tell the children to imagine they have won a holiday competition, and for their prize they can choose one of five destinations on offer. Show the children the photo activity cards.

In order to make their choices the children will need to find out about the weather and activities at each destination, through discussion and using the activity cards.

Main activity

Children work in groups with a set of photo cards, tourism cards and climate cards. They need to match each photo with the corresponding climate and tourist activity card and choose which holiday they would like.

The activity can be simplified for lower ability groups by using the simple climate activity cards.

High ability children can be challenged to match each climate description to a corresponding average weather graph.

Children tell the rest of their group their chosen destination and give reasons for their choice.

Plenary

Ask each group to match one photo to its corresponding activity cards. Ask individuals about their choice of destinations and to give reasons.

Lesson resources

Activity cards

Activity answers

Web page reproduced with the kind permission of the Met Office.

Rainbows are beautiful arcs of colour in the sky.

Rainbows are beautiful arcs of colour in the sky. Many people use the phrase ‘Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain’ to help them remember the colours of the rainbow.

Many people use the phrase ‘Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain’ to help them remember the colours of the rainbow.